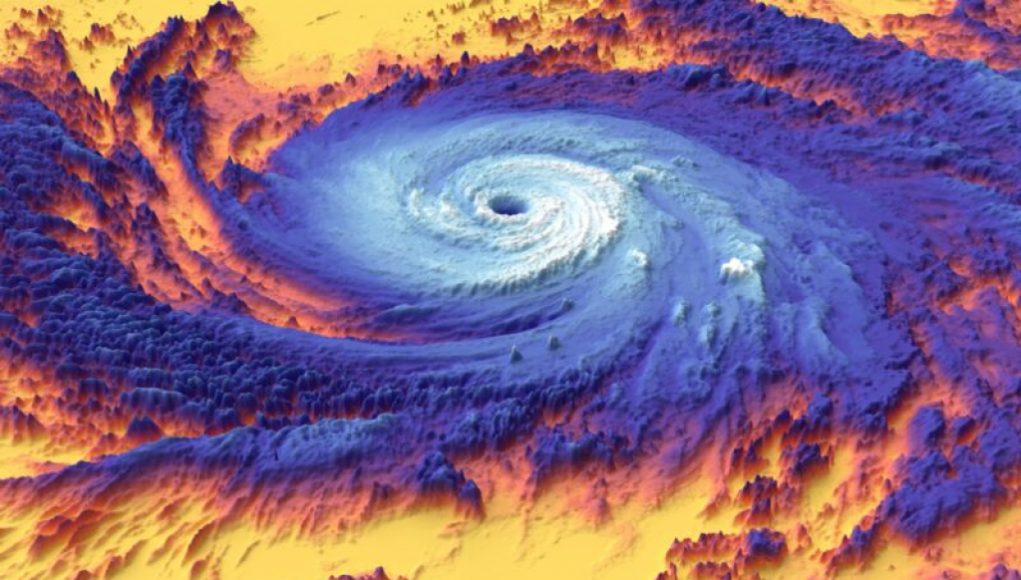

At sea, looking for typhoons

As ocean scientists, we study turbulent mixing in the ocean and the hurricanes and typhoons that generate it. In the fall of 2018, we spent two months aboard the research vessel Thomas G. Thompson, recording how the Philippine Sea responded to changing weather patterns.

During the first half of our experiment, the skies were clear and the winds were calm. But in the second half, three major typhoons stirred up the ocean, allowing us to directly compare its motions with and without the influence of the storms. We were particularly interested in how turbulence below the surface was transferring heat down into the deep ocean.

To measure ocean turbulence, we used a microstructure profiler that free-falls nearly 1,000 feet and uses a probe similar to a phonograph needle to measure the water’s turbulent motions.

New research conducted by experts at the University of Miami Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science has revealed that hurricanes are able to push heat significantly further into the ocean than previously thought.

The study, which was recently published in the journal Nature Communications, saw experts examine the behaviour of Hurricane Matthew, which hit the east coast of the United States in 2016. They discovered that the storm’s winds generated a powerful heat exchange process which enabled a section of subsurface ocean to rise from 500m below the surface to just 300m below.

This is considerably further than has ever been noted before. According to the study’s lead author, Ioulia Tchiguirinskaia, this represents a previously unidentified mechanism by which hurricanes can transfer heat.

Tchiguirinskaia noted that this process has the potential to cause widespread changes in ocean temperatures, as well as to disrupt deep-sea circulation patterns.

The findings are particularly significant, as they suggest that hurricanes may have a much larger influence on the planet’s climate than previously thought. Although the study only focused on Hurricane Matthew, the team believes that the results are likely to apply to other hurricane events.

As such, these findings could have important implications for our understanding of climate and could help us to better predict and mitigate the potentially disastrous effects of hurricanes in the future.