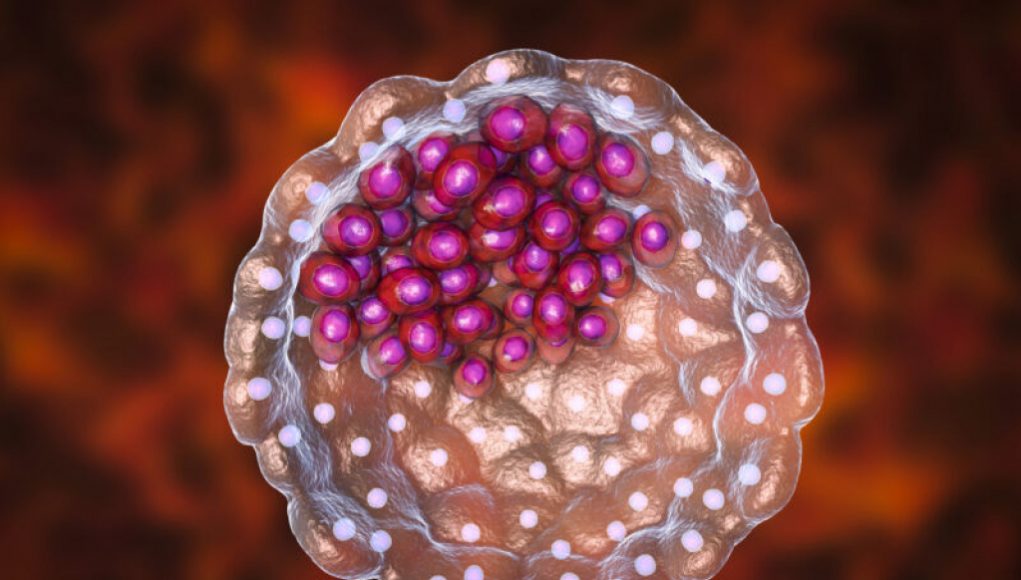

In a groundbreaking achievement, scientists have set a new record for growing primate embryos outside the womb. Monkey embryos were cultivated in a lab for 25 days post-fertilization, achieving key developmental landmarks never before observed in culture. This includes the start of organ development, which could be an important step towards understanding congenital birth defects and organ development in humans.

The early stages of animal development, often referred to as embryogenesis, are a complex and compartmentalized process. In mammals, this usually happens in the comfort and privacy of the uterus, making it difficult to observe and experiment with factors that might influence development. This has led developmental biologists to search for ways to get this process to occur in a culture dish, bypassing these limitations.

Studying human embryogenesis is restricted due to ethical and legal considerations, which is why most of our understanding of this process comes from studies of mouse and chicken embryos. However, even the mouse is more than a hop, skip, and jump away from humans on the tree of life. This is where the primate system for studying embryogenesis comes in.

Two independent groups of researchers have developed a primate system for studying embryogenesis using fertilized embryos from a macaque species. Both groups were able to cultivate primate embryos to 25 days post-fertilization, surpassing the previous record of 20 days. This allowed researchers to witness more advanced stages of organ development.

While the techniques are far from perfect, this achievement is a promising step towards a tractable system to study primate embryogenesis. The researchers documented evidence of further organogenesis and formation of the neural tube, which goes on to form the brain and spinal cord. With an optimized mix of growth and signaling molecules, combined with more advanced mechanical supports, embryos could potentially be sustained into even later stages of development.

In a groundbreaking study, scientists from the University of Tokyo have successfully initiated organ development in primate embryos in culture dishes, a major milestone in understanding how to create functional organs outside of the body.

The study was conducted using monkey embryos, which were grown in lab-made tissue culture dishes. These embryos were at a very early stage of development, and were not viable for implantation into a carrier. However, over the course of two weeks, the researchers were able to induce the embryos to develop into early-stage organoids.

This study marks a critical step forward in understanding the mechanisms that underlie organ development, and could have far-reaching implications for the development of treatments for a wide variety of diseases.

Organoids are mini organs that replicate some of the basic functions of full-sized organs, and they can be used as a model to better understand how diseases arise and spread in our bodies. Perhaps most importantly, the development of organoids like those created in this study could pave the way for growing organ tissues in a lab, and eventually transplanting those tissues into a live patient in order to treat diseases such as heart failure and kidney failure.

The specific experimental setup utilized for this study remains largely confidential, as the researchers are currently seeking patent protection for their innovative work. However, the team has released a preliminary report indicating that their success sets a new standard for organ development in a lab, which could lead to significant advances in the medical world.

Researchers are encouraged by this success, and are hopeful that further innovation can soon lead to the same results in humans. If this goal can be achieved, the implications for medical advances are staggering. In the meantime, however, researchers are focusing on using monkey models as they continue to push the boundaries in organ development research.